The Opening Chapter

The Pioneer wanted to create a world of computers and gave it the mission of executing programs. Let's help him and experience the joy of creation.

As you know from your programming classes, a program is made up of code and data. For example, a program to find 1+2+... +100, you can write a program to do this without much effort. It's easy to understand that the data is what the program is dealing with, and the code describes what the program wants to do with the data. Not to mention the complex games, what would the simplest computer look like in order to execute even the simplest program?

The simplest computer

In order to execute a program, the first problem to be solved is where to put it. Obviously, we don't want to create a computer that can only execute small programs. Therefore, we need a large enough component to hold a wide variety of programs, and that component is memory. So, the pioneers created memory, and put programs in memory, waiting for the CPU to execute them.

Wait, who's the CPU? You've probably heard of it before, but let's reintroduce it now. The CPU is the greatest creation of the pioneers, and its Chinese name "中央处理器" (Centrally Processing Unit) shows that it has been bestowed with the highest honor: the CPU is the core unit of circuitry responsible for processing the data, i.e., the execution of the program is all dependent on it. But a computer with only memory cannot perform calculations. Naturally, the CPU had to take on the task of computing, and the pioneers created operators for the CPU so that data could be processed in a variety of ways. If operators are too complicated, consider an adder.

Pioneer found that sometimes a program needs to process the same data in a continuous manner. For example, to calculate 1+2+... +100, you have to add the number and sum, and it would be inconvenient to write it back to memory every time you finish adding, and then read it out of memory to add again. At the same time there is no free lunch, the large capacity of the memory is also necessary to pay the corresponding price, that is, slow, which is the pioneer can not violate the law of material properties. So the pioneers created registers for the CPU, allowing the CPU to temporarily store the data being processed in them.

Registers are fast, but small, and complement the properties of memory, so there may be a new story to be told between them, but for now, let's just go with the flow.

Can a computer have no registers? (Suggested thinking for the second round)

Can a computer work without registers? And if so, how does this affect the programming model provided by the hardware?

Even if you've been thinking about this for two weeks, it's possible that this is the first time you've heard of the concept of a "programming model". But if you've read the ISA Handbook carefully in round 1, you'll remember that there is such a concept. So, if you want to know what a programming model is, RTFM it.

In order to make the mighty CPU a loyal servant, the pioneers also designed "instructions", which instructed the CPU what to do with the data. In this way, we can control the CPU through instructions and make it do what we want it to do.

With instructions, Pioneer came up with an epoch-making idea: can we let the program automatically control the execution of the computer? In order to realize this idea, the pioneers and the CPU made a simple agreement: after executing an instruction, it would continue to execute the next instruction. But how does the CPU know which instruction has been executed? For this reason, the pioneers created a special counter for the CPU, called "Program Counter" (PC). In x86, it has a special name, called EIP (Extended Instruction Pointer).

From now on, the computer only has to do one thing:

while (1) {

retrieve the instruction from the memory location indicated by the PC;

Execute the instruction;

update the PC;

}

Thus, we have a simple enough computer. All we have to do is to place a sequence of instructions in memory, and let the PC point to the first instruction, and the computer will automatically execute this sequence of instructions, without ever stopping.

For example, the following sequence of instructions calculates 1+2+... +100, where r1 and r2 are two registers, and there is an implicit program counter PC, whose initial value is 0. To help you understand, we have translated the semantics of the instructions into C code on the right, where each line of C code is preceded by a statement tag

// PC: instruction | // label: statement

0: mov r1, 0 | pc0: r1 = 0;

1: mov r2, 0 | pc1: r2 = 0;

2: addi r2, r2, 1 | pc2: r2 = r2 + 1;

3: add r1, r1, r2 | pc3: r1 = r1 + r2;

4: blt r2, 100, 2 | pc4: if (r2 < 100) goto pc2; // branch if less than

5: jmp 5 | pc5: goto pc5;

The computer executes the above sequence of instructions, and the last instruction at PC=5 is in a dead loop, at which point the calculation is finished, and the result of 1+2+... The result of 1+2+... +100 is stored in register r1.

Trying to understand how computers calculate

Before seeing the above example, you might have thought that instructions were a mysterious and difficult concept to understand. But when you look at the corresponding C code, you realize that instructions do something so simple! It's also a bit silly, as you can write a for loop that looks more advanced than this C code.

But put yourself in the shoes of a computer, and you'll see how it's possible for a computer to calculate 1+2+... + 100. This understanding will give you an initial idea of how a program works on a computer.

This fully automated process is wonderful! In fact, Turing, the pioneer, had already formulated a similar core idea in 1936, making him the "father of the computer". The core idea, which has been passed down to this day, is the "stored program". In honor of Turing, we call the simplest computer above the "Turing Machine" (TRM). Perhaps you have already heard of the concept of "Turing Machine" as a model of computation, but here we will only emphasize the conditions that need to be fulfilled by the simplest real computer:

- structurally, the TRM has memory, a PC, registers, and adders

- the way it works, the TRM repeats the following process over and over again: it takes an instruction from the memory location indicated by the PC, executes the instruction, and then updates the PC.

Huh? Memory, counters, registers, adders, aren't these the same parts you learned about in digital circuits class? You may find this hard to believe, but the computer you're looking at, the computer that does everything, is made of digital circuits! But the programs we wrote in programming class were in C code. if a computer is really a giant digital circuit that only understands zeros and ones, how can this cold circuit understand the C code that is the fruit of human ingenuity? The pioneer said that in the early years of computers, there was no C language, and everyone wrote machine instructions that were obscure and difficult for humans to understand, and that was the earliest way he had ever seen to program a computer. Later on, people invented high-level languages and compilers, which can take the high-level language code we write and process it in various ways, and finally generate functionally equivalent instructions that the CPU can understand. When the CPU executes these instructions, it is executing the code we wrote. Today's computers are still essentially "stored programs", a naturally obtuse way of working, and it's only through the efforts of countless computer scientists that we are able to use computers today with ease.

A computer is a state machine.

Since a computer is an assembly of logic circuits, we can divide the computer into two parts, one consisting of all the sequential logic components (memories, counters, registers), and the other consisting of the remaining combinational logic components (e.g., adders, etc.). In this way, we can understand the process of a computer from the perspective of the state machine model: at each clock cycle, the computer calculates and transfers to a new state for the next clock cycle based on the current state of the timing logic components, and the action of the combinational logic components.

What's the point of this view of the computer? Well, it doesn't seem to do much except make you realize that computer hardware isn't so mysterious. After all, ICS classes don't require you to implement computer hardware in a hardware description language, you just have to believe that it can be done.

But for programs, this perspective can be more useful than you might think.

Re-conceptualizing Programs: A Program is a State Machine

If you think of a computer as a state machine, what is the program that runs on it?

We know that programs are made up of instructions, so let's look at what an instruction is in the state machine model. It is easy to understand that the computer changes its state by executing instructions, such as executing an addition instruction, which adds the values of two registers and updates the result in a third register; or executing a jump instruction, which modifies the value of the PC, so that the computer starts executing the new instruction from the location of the new PC. So in the state machine model, an instruction can be viewed as an input stimulus for the computer to perform a state transfer.

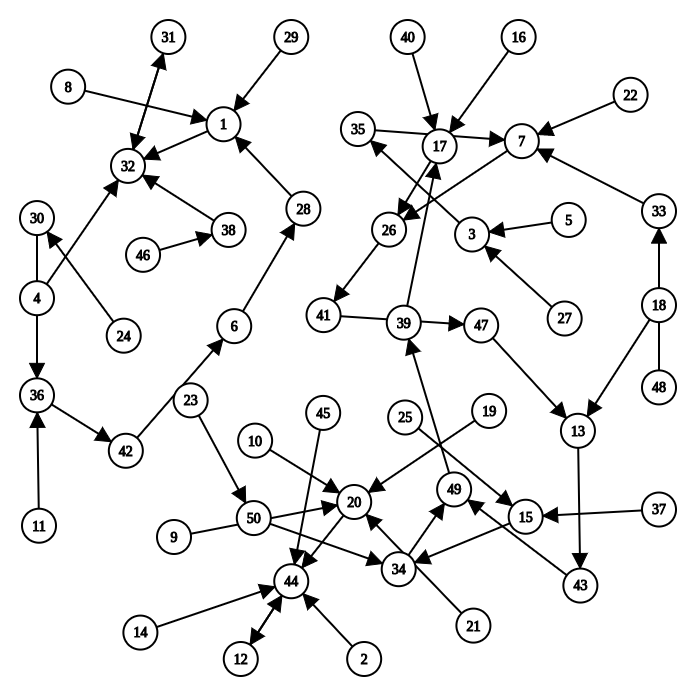

A very simple computer is described in Section 1.1.3 of the ICS textbook. This computer has four 8-bit registers, a 4-bit PC, and 16 bytes of memory, so the total number of bits that can be represented by this computer is B = 4*8 + 4 + 16*8 = 164, and so the computer can have a total of N = 2^B = 2^164 different states. Assuming that the behavior of all instructions in this computer is determined, then given any of the N states, the new state after the transfer is also uniquely determined. In general, N is very large, and the following figure shows the state transfer diagram for a computer with N=50.

Now we can explain the nature of "running a program on a computer" through the perspective of a state machine: given a program, placing it in the computer's memory is equivalent to specifying an initial state in a state transfer diagram with the number of states N, from which the program runs, with a definite transfer of state at the end of each instruction. In other words, a program can be viewed as a state machine! This state machine is a subset of the large state machine (N) mentioned above.

For example, suppose a program is running in the computer shown in the figure above, and its initial state is state 8 in the upper left corner, then the corresponding state machine of this program is

8->1->32->31->32->31->...

This program could be:

// PC: instruction | // label: statement

0: addi r1, r2, 2 | pc0: r1 = r2 + 2;

1: subi r2, r1, 1 | pc1: r2 = r1 - 1;

2: nop | pc2: ; // no operation

3: jmp 2 | pc3: goto pc2;

Understanding Program Operations from a State Machine Perspective

As an example, try to draw the state machine of the program in the previous subsection 1+2+... +100 instruction sequence in the previous subsection as an example, try to draw the state machine of this program.

The program is relatively simple, and the only state that needs to be updated is PC and the two registers r1 and r2, so we can represent all the states of the program with a triple (PC, r1, r2), without having to draw the exact state of the memory. The initial state is (0, x, x), where x means uninitialized. The instruction at program PC=0 is mov r1, 0, after which PC points to the next instruction, so the next state is (1, 0, x). By analogy, we can sketch the state transfer process for the first 3 instructions:

(0, x, x) -> (1, 0, x) -> (2, 0, 0) -> (3, 0, 1)

Please try to finish drawing the state machine, For the loop in the program you only need to draw first 2 and last 2 iterations.

With the above example of a required question, you should have a better understanding of how a program runs on a computer. We can look at the same program from two complementary perspectives.

- A static view of code (or sequences of instructions), often referred to as "writing a program"/"looking at code", is actually a static view. One of the benefits of this perspective is that it is a compact description, and the combination of branching, loops, and function calls makes it possible to achieve complex functionality with a small amount of code. But it can also make understanding program behavior difficult.

- The other is the dynamic view of state machine state transfer as an effect of operation, which directly portrays the nature of the "program running on the computer". However, the number of states in this perspective is very large, and all the loops and function calls in the program code are fully expanded at the granularity of instructions, making it difficult to grasp the overall semantics of the program. However, the state-machine perspective gives us a clear understanding of the details of the local behavior of a program, especially the behavior that is difficult to understand from a static point of view.

What are the benefits of the state machine perspective of a program?

Some programs may look simple, but their behavior is less intuitive, such as recursion. To get a good understanding of how a recursive program works on a computer, it is most effective to look at the program's behavior from a state-machine perspective, which helps you understand how each instruction modifies the state of the computer, and thus the semantics of recursion at the macro level. Chapter 3 of the ICS theory course is devoted to the details of this, so we won't go into the specific behavior of recursion here.

A microscopic view of "programs running on computers": the program as a state machine

The "program as a state machine" perspective is important for both ICS and PA, because "understanding how programs run on computers" is the fundamental goal of both ICS and PA. The macro view of this problem will be introduced in the middle of PA.

The text in this subsection should be easy for you to understand, but if you don't develop a sense of understanding program behavior from a state machine perspective in the future, you may find PA very difficult because you will be dealing with code constantly in PA. If you can't understand the behavior of some key code from a micro perspective, you won't be able to fully understand how a program works from a macro perspective.